BY IAN SPULA

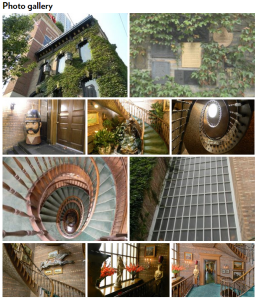

Flair House and Flair Lane (Honorary Lee L. Flaherty Way) PHOTO: IAN SPULA

PUBLISHED AUG. 28, 2015

For the first time in 51 years, the 132-year-old Flair House at 214 W. Erie Street in River North has changed hands.

Click Here to read the original article On Chicago Magazine .

Flair House is house in name only. Lee Flaherty bought the structure in 1964 for $20,000 and used it for his marketing agency, Flair Communications; commercial use will continue with the new owner. What counts is stewardship, and Flaherty has looked after this brick townhouse like an ancestral treasure.

The attachment goes beyond years, though five decades is nothing to scoff at. “I would drive to my place on the South Side and this fatigue green building called out like a siren,” Flaherty says. “Over my protests, my mother mortgaged her house to give me $8,500 toward the purchase. She just said ‘I want you to work hard, keep your integrity, and give back when you’re successful.’” Most famously he gave seed money for the first Chicago Marathon in 1977 and financed the second, though the list of charitable gifts is long.

Flaherty named the building’s main social space the Frances Room for his mom. It includes a new wet bar and trompe l’oeil walls depicting Gold Coast mansions—Palmer’s, Field’s, McCormick’s, et al.

In 1964 the house, built by milk merchant Marcus Devine, had no electric, no plumbing, and definitely no air conditioning. That quickly changed, and as Flair Communications grew in the late 1960s, Flaherty plotted an annex to house more staff where half of the house had burned to the ground in the 1929, bringing the square footage to 7,000. The annex is integrated with the old front half by a four-story light well with a gigantic wooden spiral staircase—handcrafted by two German-American carpenters brought out of retirement for the job. The annex also includes a rooftop deck and garden with sweeping views south and east. Eventually, Flair House would be for company executives, with another 300 staff down the block.

Flaherty was exceptionally careful about who came in after him, since the house is not landmarked. Twelve offers were declined in one year on the market until “the perfect buyer said ‘we want to buy everything including the soap in the soap trays.’” That was David Blitz of Blitzlake Partners, a real estate acquisition and development firm, and “everything” included over 100 paintings and sculptures, truckloads of antique furniture, and a 2000 Rolls Royce. The art is varied but there’s an emphasis on Greek mythology in the sculpture, and landscapes in the painting. Flaherty also has a bunch of original Parisian Art Deco posters. And nearly 200 of these framed posters fill common areas at neighboring Flair Tower, an 26-story apartment building where Flaherty has lived since its 2010 completion.

Flair Tower and Flair House fall under one Planned Urban Development (PUD). Flaherty sold the developer the parking lot he had owned just west of Flair House with the stipulation that its lower floors reflect the house in materials, and he got the Flair name affixed to the tower. As part of the same PUD, some extra air rights shifted to Flair House during development. An owner can theoretically build another two stories and 2,300 square feet of live/work space, something Blitz may consider down the road, according to RE/MAX’s Katie Barreto, broker for the buyer and seller.

The impact Flaherty had on one forgotten house is a microcosm for his role in ushering River North from an industrial “mud flat with broken sidewalks” to the upper echelon status it enjoys today. “You wouldn’t catch women in the neighborhood back then.” He is even widely credited with naming the neighborhood. “We started promoting our location as River North in business circles. It caught on.”

Flaherty listed in July 2014 for $2.99 million and closed this week for $2.73 million. Were this a fully updated 7,000-square-foot River North residence with five or six bedrooms, it would command closer to $5 million.

“Fifty years went by in the blink an eye. I love this place but it got too comfortable, in a way,” says a sanguine Flaherty. “I needed to be disruptive so I left the brick and mortar behind.”